BEYOND THE REMODELING

HELP! WHERE DO YOU GET A FREE PIANO?

The Playhouse would open in a couple of weeks, and we desperately needed a piano that was in good enough shape to stay in tune and that didn’t cost anything. Money for a piano was never in the budget.

Fortunately, someone knew someone, or maybe it was a church, who had an old upright piano they were happy to get rid of–for free! One day the guys took a truck and retrieved the piano which then had to be lugged up the steps to the second-floor theatre (The ramp wasn’t built until 1979.) and then down the seating platforms to stage left in front of the proscenium. To our knowledge, no one incurred a hernia in the process. A piano tuner was called, and that piano was used for several seasons.

Our early pianos were all uprights and were left in the barn over the winter. The cold, hot, and damp meant the pianos didn’t last long, a couple of years max. They were surely workhorses, but their harsh treatment meant their keys would warp and the ivory would pop off, the strings would rust, and their once-lustrous finish dulled and peeled. Regardless, no one in his or her right mind was going to suggest taking one of those pianos back up the seating platforms and down the steps then to someone’s home for winter storage. This meant that we had to solicit for a new piano every several years. Of course, when we replaced one piano with another, the dreaded removal process had to be executed. It was horrible, requiring five or six strong guys willing to risk a hernia. When one piano became too weathered to stay in tune, we’d ask everyone we knew about donating a piano. The word got around, and someone would have an upright they were happy to donate.

Over the years, we asked for donations of numerous things—working refrigerators, sewing machines (We received 5 on the first appeal and never had to ask again while I was there.), formal wear, and various other items. We were never disappointed. Recently, I was thinking how much easier the “begging” process for needed items would have been if we had had email, Twitter, Facebook, and other digital platforms back in the days when I was at the Playhouse (1972-1995).

Finally, in the late 1980s, I got a grant to pay for a nice electric piano that could be easily moved and stored in someone’s home over the winter. It was an immense improvement over the heavy, bulky uprights. I hasten to add, however, that those old uprights served us well for a number of years, and those who donated them were much appreciated.

SELLING THE SEATS

Someone came up with the idea of Selling the Seats. For the grand price of $25, one could get his or her name on a small brass-ish plate that would be attached to one of the wooden arms of the theatre seats. Of course, it was a way to make a little more money, and we had some success with the venture. At the end of the season, I made a decoupaged, wooden plaque with the names of the donors. Sadly, we reneged on the seat plaques.

At the beginning of the 1973 season, the plaque was bolted on the lobby wall and we encouraged more people to spring for a seat. As others donated, their names were added. The plaque lasted that one season. When we returned in the spring of 1974, the plaque had been pried from the wall and probably used by some picnic group for firewood. Sadly, we hadn’t kept a master list of names (we had the plaque, didn’t we?), so that was the end of that brainstorm!

THE LIST

As we sold season coupons, we started a mailing list. We didn’t sell that many season coupons that the first season, but it was a beginning, and the list did grow. Norma would be shivering in the box office (It was so chilly at night that first season that she brought an electric heater from home to keep her feet warm), but she would ask ticket buyers if they would like to sign up for the mailing list, and many did.

After we had set the plays for the 1973 season, I composed a newsletter that went out to our mailing list members. The newsletter announced the season and the availability of season coupons—the perfect gift for any occasion. We had those early newsletters reproduced by our printer, Ray Mester of The Follansbee Review.

The first year or so, we folded and addressed the newsletters by hand. The mailing list wasn’t actually a list. We transferred the names and addresses to index cards. This was we could divide up the cards, give someone 20-30 cards, stamps, and unaddressed newsletters, and that person would fold, address, and stamp the newsletter and return them to me for mailing.

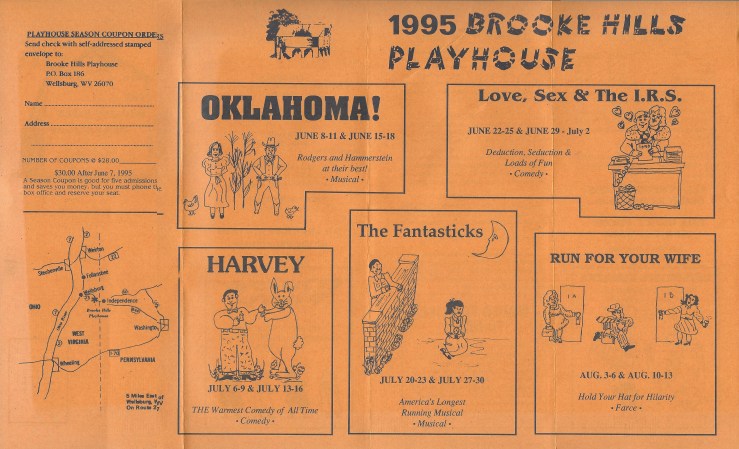

Note the drawings by the multi-talented Russ Welch.

AIR-CONDITIONED BY GOD

When we first looked at the barn as a possible theatre back in November of 1971, Bill Harper was able to ascertain that the size of the barn would fit our needs and that the basic structure of the barn was still in great shape, even after maybe 100 years. One end of the barn on the first floor had been closed in to create the public restrooms for the ox roast celebrating the centennial of West Virginia. The opposite end of the first floor, however, where we planned to put the dressing rooms and the tool room/kitchen, was wide open and would have to be closed up. A lot of the siding on the second floor was in terrible shape. Haha! More than that. In many places, there was no siding!

The barn was sided with vertical boards–16′ x 12″ boards on the top and 12′ x 12″ boards on the bottom. The cracks between the adjacent vertical boards were covered by long pieces of lath.

At some point before we arrived, one large portion of siding on the yellow house side of the barn had been replaced. Unfortunately, it had been replaced with horizontal tongue-and-groove siding and stained a reddish-brown that in no way matched the dark brown/charcoal grey, weathered, vertical siding on the rest of the barn.

Note the open end where the dressing rooms and kitchen/toolroom would be carved out.

I know that we rented scaffolding, and I know that there were some spaces between a lot of the siding boards, but for the most part, we patched the hundreds of places where boards were missing by opening night. We were never going to be able to patch all the spaces, so we said the barn was “air-conditioned by God.”

It’s funny, but I have no recollection of patching all those holes. I asked several others who worked that first year—Bill Nelson, Larry Crofford, Norma Stone, Janie Miller, Judy Hennen, Tom Cervone, and Tom Pasinetti, and none of them remembers patching the barn walls either. Norma said, “There was an old barn being taken down or it had fallen down somewhere. A local person found out about it, and we got the wood. That’s all I can remember.” That rang a bell with me, and in my mind, I can picture a big pile of old wood stacked out behind the barn. I imagine that wood filled up many of our gaps.

That first year and for several more, the audience would park and enter from the Kiwanis Shelter side of the barn. Seeing the old structure for the first time probably did not inspire confidence in those coming to see a show.

I have often wondered what our audience members thought the first time they walked from the shelter up the sidewalk to the barn. “Good grief, we’re going to be crushed when this thing collapses!” “It really is a barn! How good can it smell?” “Is my life insurance paid up?”

Once inside, however, the strength of those massive, hand-hewn 12″x12″s supporting the structure with their diagonal struts holding up the large overhead joists had to alleviate most fears. Hopefully, once the show started, the building melted away, and the audience was caught up in the action onstage.

NOTE: In 1984, I was able to get a historic preservation grant, and we resided the barn with new treated lumber.

A SAD NOTE

One of the West Liberty drama/music students who came and helped out a few times in those first two months during the Playhouse remodeling was Jim Sheets. I don’t know if he auditioned that first season, but it seems to me that he didn’t have reliable transportation, so getting to rehearsals would have been difficult.

Al de Jaager, a West Liberty professor now retired and living in Cambodia, takes over Jim’s story:

Jim was, of course, in my Concert Choir. We were in Spokane, Washington, singing at the EXPO (International Exposition on the Environment, World’s Fair) in 1974. Jim was spotted by one of the producers there and asked to stay on, so we returned to West Virginia without him. While he had been assured work in Vegas, that didn’t pan out, so he went to California. Like most, he worked as a waiter, got to shoot some commercials, and was in a performance at the Hollywood Bowl.

The star at the Hollywood Bowl performance was a well-known female, but I can’t remember who that was. Jim’s voice was outstanding, so he was again spotted. This time it was for the New York company of Les Miz. But first he was needed as a stand-by for Jean Valjean in the Australian company. He said it was great. At show time he had to be within 20 minutes of the theater in the event the star was not going on.

Jim spent lots of time on the beach, and then it was off to be in the New York company. As the stand-in for Jean Valjean, he would perform that role at least once a week. It is a very demanding role, expecting the singer to pop out a high B♭ shortly after appearing on stage, not something just any baritone can do.

He arranged to do the lead each time I went to New York, even though, as I found out later, he may have had to pay the lead to do that. We would then meet up for a drink at a nice little bar on 9th Ave.

I am told that Jim was headed to visit his spot in the Poconos while enjoying some time off. He stopped to buy some things, came back to the car, got in, and was gone. I’m glad he didn’t have to suffer. Those of us who loved him still do.

Stanley Harrison and I attended his memorial service held at the Majestic Theater in NYC. The tributes were overwhelming. They all agreed that no one sang the role of Jean Valjean better than J.C.

I also attended his memorial service in Wheeling. I knew his sister-in-law, and I mentioned that I had often visited with J.C. (James Courtney Sheets) in NY. She said she knew because he kept a log of those who visited him in NYC. She said my name appeared often.

When I visited NYC, I liked to host a Saturday brunch for former West Liberty folk. This is a photo from the 2006 gathering. It was the last time I would see Jim. He was a fabulous baritone, a wonderful human being, and a dear friend.

According to the International Broadway Data Base (www.ibdb.com), from March 12, 1987 to May 18, 2003, Jim appeared night after night in Les Misérables replacing a Chain Gang member, a Sailor, Brujon, the Other Drinker, and eventually, as the understudy for the lead Jean Valjean, when as Al said, he played the lead at least once a week.

One year, Tom Cervone (T.C.) and his wife Susan were in New York and went to see Les Miz, hoping that Jim would be replacing someone that evening. He was, and it was Jean Valjean. “He was great,” said T.C. and we met up afterward—also great.”

Jim’s obituary in PlaybilI tells more of his story:

J.C. Sheets, an actor-turned-dresser who spent his career working two Cameron Mackintosh mega-musicals, Les Miserables and The Phantom of the Opera, died Feb. 4, 2007, of an aneurysm.

Mr. Sheets joined the Broadway company of Les Miz in 1988 and stayed, on and off, for some eight years. He began by playing the role of Brujon, but would go on to fill 12 different ensemble roles. His biggest responsibility was as alternate and understudy for the lead role of Jean Valjean. He portrayed Valjean more than 300 times on Broadway.

Following his Les Miz tenure, he jumped to Phantom in a new guise, as a dresser in charge of the costumes worn by the actor portraying the Phantom. In this capacity, he dressed such actors as Hugh Panaro and Howard McGillin. He worked backstage at the show until his death.

In addition to Les Miz, Mr. Sheets acted Off-Broadway, regional theatre and in five road shows, including Peter Pan with Sandy Duncan, Annie Get Your Gun with Debbie Reynolds, and Camelot with Richard Harris.

Sadly, Jim never performed on our stage, he just helped to make it possible.

Wonderfully written, Shari!

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Kay. Miss you?

LikeLike

Great as usual. Book?

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Thinking about it.

LikeLike

What a great talent and so sad he died so young. I would love to see that barn some day !! What great memories and lasting friendships bonded in a barn!

LikeLike

Pam, I just love that you read my blog. That old barn is a keeper! I’d love for you to see it.

LikeLike

Also, “Bonded in a Barn.” Great title!😍

LikeLike