Cigarette in mouth, champagne in hand, big grin on face!

BILL MADE IT COME TOGETHER

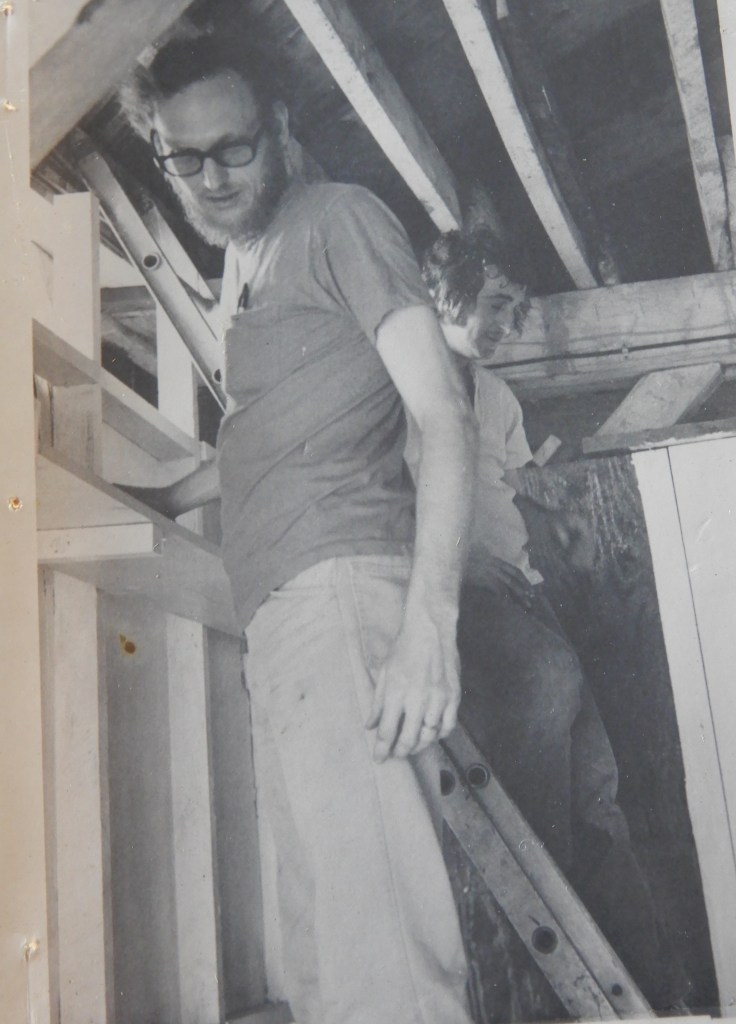

While John, Judy, I, and all the staff and volunteers were right there with him, Bill Harper was really the driving force behind the barn-to-theatre conversion. He knew what needed to be done and how to do it. He also knew the order that had to be followed in order to get it done. He made what seemed like thousands of work lists for us to follow while he worked tirelessly with his dad (Bill, Sr.), Bill Nelson (Nelly), John Hennen, and a lot more of the guys to get the really heavy work of the remodeling finished—beams removed, steel installed, massive stairways moved, seating platforms built, seats installed, and so much more.

In addition to being the brains behind the barn-to-theatre transformation, Bill did so many other things. One of his genius concoctions was our first light board. It was definitely one of a kind, and It was lovingly and respectfully dubbed “Old Sparky.” How I wish we had a photo of it!

Somewhere along the way, Bill had accumulated 12 old, rotary rheostats which were approximately 10” in diameter. He mounted the rheostats in two rows on 2”x4”s. The 2”x4”s with their “cargo” were installed on the concrete floor in the hallway against the men’s dressing room wall. Bill had someone attach a bent pipe to the rod which controlled the rheostat which in turn dimmed or brought up of the lights. The pipe was bent like a lightning bolt with two 90ᵒ angles. The bottom of the pipe was attached to the control handle on top of the rheostat.

A rheostat. The Sharpie mark shows the piece of pipe that was added to serve as a “handle.” The handle was attached to the rod that would turn and control the dimming or lighting of the stage and house lights. In your mind picture two rows of six of these.

Cables were run from the pipes upstairs where the lights were hung over the audience and the stage to the barn wall on stage right, down through a hole in the floor, across the ceiling of the first floor, and down to the rows of rheostats. The rheostats could be worked independently, and with the help of drilled 1”x3” pieces of wood, the rheostats could be worked in tandem, which required a lot of practice.

Someone named the contraption “Old Sparky,” but honestly, it never sparked. At least I don’t remember it ever sparking!

The house lights were old wheels that had been wired with sockets and light bulbs and hung by the W. Va. Centennial Committee. Those lights had to have their wiring re-routed down to Old Sparky in the “light control room.”

The light board operator or operators (it sometimes took two people for a blackout) couldn’t see the stage, so the stage manager had to call the cues over a headset communication system that Bill had picked up somewhere. It dawns on me that I never questioned where he had acquired a lot of this stuff. I guess I didn’t want to know, but it all came in handy. We used that lighting system for several years before Bill came up with a more compact light-dimming system that the stage manager could control from just behind the proscenium on stage left.

Bill had a lot of theatre “stuff,” including the massive, velvet act curtain from the White Barn Theatre rubbish heap. It would have been a really big job to cut it down to fit the Playhouse stage. Then someone would have had to hem it while inserting a chain in the hem for weight in the bottom. I’d already hemmed that darn curtain once when I worked at the White Barn, and I wouldn’t wish that job on anyone! AND the long and heavy drapery track would have to be cut down to fit our stage before it could be mounted behind the proscenium. It just wasn’t worth the effort. Bill told John and me, and eventually, he told the crew that we wouldn’t be using an act curtain–ever.

Ironically, this turned out to be a great idea, as over the years, our audiences have strained to see and loved to watch the quick, “choreographed,” scene changes in dim light. Occasionally, the scene changes have even received appreciative ovations!

Another of Bill’s bright ideas we all had trouble visualizing at first. Bill had determined that we couldn’t afford to build and paint standard theatre flats (wooden frames covered with unbleached muslin) for box sets (representing an apartment or living room, for example). Instead, we would paint and texture 1”x3” wooden boards. The painted 1”x3”s would be placed upright on the stage wherever there was a corner or angle in the walls of the room. 1”x3”s would be affixed to the top and bottom on those corner uprights, like crown molding and baseboards. Whole door frames and doors and windows would be “free-standing” (secured backstage). Black burlap was then staple-gunned to the back of all the 1”x3”s, doors, and windows. In other words, walls were just suggested by the framed burlap, but the audience believed in the “walls” from the git-go.

Here are a few of the sets in those early years that use the “batten and burlap” style of scenery:

The crews loved this scenery because the burlap acted like a scrim. When the stage lights were up, all of us backstage could watch the show and not be seen. No one ever missed an entrance! We started using some real flats, opaque scenery, in 1975, and the crews hated just listening to and not being able to watch the show!

Bill Harper really was the driving force behind the creation of Brooke Hills Playhouse. John Hennen and I quickly bought into his dream, but Bill made all the plans. I still have my copy of the 10-page letter that he wrote to John, Larry Lebin, and me in late 1971, shortly after we had permission to use the barn. The letter is typewritten and single-spaced. It lays out numerous details, ideas, plans, and a woefully optimistic and inadequate budget. By the way, Larry Lebin was a West Liberty friend of Bill and John who had initially planned to join in the Playhouse venture. He would have been a fourth investor, but he dropped out shortly after receiving this letter.

Bill and I had met at West Liberty State College in 1967. He was a senior, and I was a sophomore. We both worked at the White Barn Theatre, a summer stock theatre outside of Irwin, Pennsylvania, that summer. We started dating then, and we married in June 1972, in the middle of transforming the old barn into a theatre. Our son, Andrew, was born in 1981, and we divorced that same year. Bill left the Playhouse at the end of the 1981 season, and I became the Managing Director for the next 14 years, leaving in 1995 when I remarried and moved with Andrew to California to join my husband Richard Coote and his two sons, John and Kevin.

Bill loved The Theatre, The Drama. He had caught the theatre “bug” while a student at West Liberty State College, and he dedicated his life to it. Sometimes he had to take side jobs to support his theatre habit, but putting on plays and concerts always came first for him. He was supremely talented, not onstage but backstage, as a designer, carpenter, welder, and electrician. His knowledge of structures and load distribution, and his ability to draft the plans for the barn’s transformation (always approved by the county engineer) were mighty impressive. Bill’s energy and drive to get the Playhouse up and running inspired many others to try and work as hard as he was working.

Without William Wilson Harper, Jr., Bill, there would have been no Brooke Hills Playhouse. I think he would be proud to know that 50 seasons of shows have now been produced in the theatre he created.

May 13, 1943–November 12, 1996

Al great and well deserved tribute to Bill Harper. I loved this.

LikeLike

He really did keep us all working and moving forward.

LikeLike

Really nice memorial. Thanks yet again.

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

I really appreciate your comments. You’re welcome!

LikeLike

It was amazing all the work behind the scenes and up front. Jeepers. You were very lucky to have Bill to help. Didn’t he also have some connection with lighting or perhaps it was the light board? Cheers, Marti

LikeLike

He toured with a lot of rock bands–Alice Cooper, Judas Priest, Black Sabbath, and worked on their lighting.

LikeLike